In search of lost times (I)

- Introduction :

- Sâm Thuong, writer, playwright, and one of Trinh Cong Son’s closest friend who had always been by Son’s side during Son's very last years, has begun his memoirs of the composer’s life. In memory of the third anniversary of Trinh Cong Son’s death, Sâm Thuong has exclusively granted tcs-forum.org the privilege to present on line Part One of his memoirs: from childhood until Son turned nineteen.

Part one : Childhood

One month after the Munich treaty (1), Japan began the Southward March by occupying Guangzhou and isolating Hong Kong from mainland China. On February 12, 1939, Japanese troops moved into strategic bases east of Hainan Island near the Indo-China seashore colonized by France, and to Sinam Island in the Spratly archipelago.

By spring 1939, the German Third Reich moved its troops to the borders of Czechoslovakia, and on March 13 of that year invaded its capital Prague. One month later, on April 7, the Italian army conquered Albany in the Balkans. The weakened European nations failing to come up with a self-defense strategy must turn back to a few smaller eastern European states to establish the “last belt of defense for peace”. On April 13, 1939, England and France signed with Poland a military alliance accord. But by April 28, 1939, Germany did away with both its Treaty of Non-Aggression with Poland (2) and the Anglo-German Peace Agreement (3).

On May 25,1939, Hitler and Mussolini signed the Pact of Steel (4) that sealed the absolute alliance between Germany and Italy. The Third Reich began to threaten Poland and reclaim the port of Dantzig Strip located deep inside Polish territory. The Second World War was set in motion, engendering destruction more horrific than any that had occurred before.

Meanwhile, Vietnam was living under the yoke of colonialist France, a France that was crushing the indigenous people but trembling under the raising force of the German fascists. Trịnh Công Sơn came into this “ impermanent world” under such international and national geopolitical circumstances.

Trịnh Công Sơn was born on February 28, 1939 in Daklak in the central highlands. His father was Trịnh Xuân Thanh and his mother was Lê Thị Quỳnh. Daklak was not really his hometown, since previously both his parents had lived in Huế in Thừa Thiên Province. Their family was originally from Hương Vinh hamlet in Minh Hương village in the district of Hương Trà. Trịnh Công Sơn’s father was a patriot who could not tolerate the harsh and savage regime the French inflicted on his people. He carried out secret activities that supported the Resistance and antagonized the French. His father did not belong to the communist movement but was simply a man who loved his country like many of his fellow countrymen of the time. Because the French secret service constantly watched him and caused him trouble, in 1937 he quietly moved to Daklak with his wife. Here he opened the Kam Tik tailor shop on Nguyễn Thái Học Street (now Điện Biên Phủ Street), next to the Buôn Mê Thuật movie theatre.

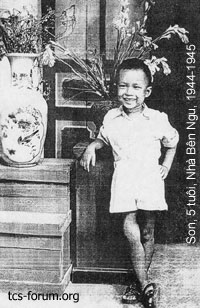

Trịnh Công Sơn was not the eldest child of this young couple who moved from Huế to establish a new life in Daklak. Sơn had a brother, Trịnh Xuân Dương, who was born three years before him in Huế, but Dương died when he was two months old. After his brother's death, Trịnh Công Sơn obviously became the eldest son in the Trịnh family (5). Sơn’s family did not stay long in Daklak. When he turned four, his family moved back to Huế and settled into a house in Bến Ngự.

Summer 1944: after France’s liberation, De Gaulle and a free France were faced with the task of building a post war policy towards its colonies. France's goal under De Gaulle was to get rid of Japanese military rule, return to Indochina, and set up a political system in which the monarchy would be represented, but in substance the controlling power would still reside in the hands of the French protectorate.

Autumn 1945: When Trịnh Công Sơn turned six and was ready to start school, he witnessed the Ất Dậu famine, then the Japanese surrendered to the Allies and the August Revolution broke out. Sơn attended Trần Quốc Toản Elementary school (Thành Nội, Huế) for a year before transferring to Nam Giao school. During this time, his family lived at Bến Ngự. To get to his home, you crossed the Bến Ngự bridge and went straight ahead on Phan Chu Trinh Street until you reached Nguyễn Hoàng Street (now Phan Bội Châu Street). Then you crossed the railroad tracks and went straight up the hill. On the first alley on the left was a house with a water well. This was Sơn’s house. Today its address is 43B Phan Bội Châu, Huế.

Two places not too far from Sơn’s house played an important role in his childhood, and he often spoke of them with his close friends. To get to the first spot, when you crossed Bến Ngự Bridge, rather than going straight on Nguyễn Hoàng Street, you turned left on Phan Chu Trinh for about 55 yards. There you would find a French garrison. Anyone suspected of carrying out anti-colonialist activities had to pass through this garrison. Every night the neighborhood would hear the screaming and agonized cries of the detainees being tortured. In particular, in front of the garrison stood a golden apple tree that bore green fruit all year round. Either because they felt teased by the green fruit or because of some other subconscious reasons, children, including Sơn, would invariably throw rocks at the tree each time they passed by. They would not run away until the French came out with guns in their hands.

The second spot on Nguyễn Hoàng Street was a small alley just on the other side of the railroad tracks that ran parallel to them. At the corner of this alley and Nguyễn Hoàng Street stood an ancient tropical almond tree with a huge trunk and thick foliage that concealed a patch of sky. Many early mornings agitated locals would gather around this tree to witness sights of slashed corpses, French and Vietnamese alike, hanging from the tree, heads fallen backwards, with words written in blood across the front of their shirts or on banners: “Punishment reserved for Viet traitors” or “ The invader must pay for his crime”. Those words and sights would always attract the troubled attention of the locals as well as of the young pupils like Sơn. Before getting to school, Sơn would follow his friends to sneak a peak at those scenes, then he would leave quietly carrying his own thoughts that probably were still undefined…

Another reality directly affected Sơn’s thinking and action, forcing him to face history’s verity. That was his father’s life and brutal fate. According to Sơn, from 1945 until 1949, every year for five consecutive years, every time some sign of social unrest surfaced, his father was arrested and imprisoned at the Thừa Phủ jailhouse in Huế. “ During this time, in Huế, my mother and I took turns visiting him, and in 1949 I got permission to join my father in the Thừa Phủ jail, one year before the whole family moved to Saigon” (6). When he saw his emaciated father walk out of the jailhouse, his body ridden with gashes, in tears he would embrace his father, his heart filled with pain and hatred. Those images never faded in his memory. They would pursue him, they would cling to his life, and later they would haunt the music he composed.

Sơn and his generation were still too young to understand and bear responsibilities for the historic reality that unfolded in front of their eyes. In 1949, although it was said that “ the whole family moved to Saigon”, actually when his father opened an office in Saigon to expand his business, he took only Sơn and Hà with him, while the others would join them the following year. For a while at the beginning, Sơn and his family lived on Calmette, Tân Định (now Đinh Công Tráng Street), then they moved to Dypre (a small street that crossed Nguyễn Trải Street), and finally they relocated to Parinol Street (now Đặng Trần Côn Street). In Saigon, Sơn attended sixth grade at Hưng Đạo School on Cống Quỳnh (1949-1950). Then he transferred to the French high school education system and attended Jean Jacques Rousseau School until he passed the Brevet (1950-1954).

By August, 1954, after the signing of the Geneva Accords, Sơn’s entire family returned to Huế and opened a shop called Thanh Tâm on Hàng Bè Sreet (now Huỳnh Thúc Kháng). Later it was moved to 79 B Gia Long Street (now Phan Đăng Lưu). This business involved the distribution of parts for bicycles and motorbikes to dealers in Huế and the surrounding area.

After his return to Huế, Sơn attended the Lycée Francais for a year, then he moved on to Providence School (Thiên Hựu), and graduated with the Baccalaureate I (Bac I) in 1955-1956. Providence School was one of the three large private schools managed by the Catholic Church. At the time, only well-to-do families in Huế could send their children to either Providence, Pellerin (the boys' schools) or Jeanne D’Arc (a girls' school). During this time, Sơn was exposed to works by Alfred de Musset, Alphonse Daudet, Anatole France, Saint- Exupéry etc…

Though he enrolled in the French program and was educated under the French system, Sơn and his generation witnessed the division of his country at the Bến Hải River demarcation line. Once more, he and his generation were not responsible for this wrenching situation. He was not mature enough to seek the reasons that led his forefathers to shoot at each other and consider each other enemies.

Following the Geneva Accords bloodshed stopped for a while, but then a national general election set for 1956 was cancelled, and bloodshed and killing resumed. Sơn and his generation grew up under the seemingly peaceful regime of Ngô Đinh Diệm. They were raised and educated in the South, by the southern regime. I use the term "educated" in its broadest sense—to include communication and propaganda.

The truth could not be denied: through the American arrangements, Ngô Đinh Diệm’s regime had inherited half of the territory previously under French domination, a territory harboring a society in which old values had collapsed and degenerated. It was tragic that the South could not come up with any doctrine to fill the void that was left. In fact, Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime did realize the problem, and had attempted to come up with a controlling dogma, but that dogma was really only an imitation borrowed from the Personnalism theory of Emmanuel Mounier (7).

Reality had showed that Diêm’s Personnalism did not meet the historic needs of the people, nor did it fit with humanity’s evolution as an all-encompassing directive serving as the foundation for conceptual and social organization. Although the intent of Ngô Đình Diệm's regime was to forge a younger generation of anti-Communists, it cannot be denied that their education system cultivated laudable ideas such as patriotism, the indomitable will to fight aggressors, and the realization that Vietnam is one single S-shaped land running from Nam Quan Pass to Cà Mau Cape; it is not the oddly shaped half nation as drawn on the American military maps or in textbooks distributed by the U.S.A at the time.

Though those lessons were hailed only in words, they nevertheless strongly influenced the minds of the young generation in the South. Images of a Nguyễn Huệ, a Hoàng Hoa Thám, a Phan Đình Phùng, Nguyễn Thiện Thuật, Nguyễn Trung Trực etc. always were presented as glorious heroes saving the nation.

For that whole period, Sơn and his generation had been blinded and forbidden to learn anything about the second resistance war against the French in which his elder’s generation had participated. They knew nothing of the socialist North, except what Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime wanted them to know.

Sơn, like other youths his age in his town, grew up by the Perfume River and the Ngự Mountain. Everyday, he watched time leave its imprint on ancient palaces, the Tràng Tiền bridge with its six arches and twelve spans, the boats streaming to and fro, the long roads lined on both sides with green camphor trees and clusters of red flame tree flowers, girls in white dresses (áo dài), wearing their tilted conical hats on the way to school, the lingering rain... Still melodious to his ears, the Buddhist chanting, the temple bell resonating at dawn and at dusk, the rhythmic lullabies echoing from the river—all that had plunged him into his own dreamy world filled with longings. “At the time, I was a little boy who loved to sing. At ten, I knew the solfege, I copied my favorite songs and bound them into books, and I played the mandolin and flute. At twelve, I got my very first guitar, and ever since then I have been using the guitar as a common instrument to accompany myself ” (8).

In June 17, 1955, Sơn’s father along with Mr. Lộc Lợi and Mr. Lê Văn Tông (his mother’s younger brother) rode their motorbikes from Huế to Quảng Trị, on their way to expand their businesses. As his father was manipulating the vespa, a truck hit him and he died a few hours after he was transported to the hospital.

His father had shouldered all the family’s needs. He was indeed the pillar of the family. He provided for Sơn and his siblings a life that if not affluent was comfortable in comparison to that of Sơn's peers, especially in a small and quiet town like Huế. All this was the fruit of his father’s labor. Sơn’s family was among the first to own a phonograph when this appliance initially appeared on the market. The death of his father dealt a hard blow to Sơn. He himself has confessed: “In my childhood, I was obsessed with death. Many nights in my sleep I would dream of my father’s death” (9).

While in mourning, Sơn completed his Buddhist initiation rites at Phổ Quang Temple, and was baptized Nguyên Thọ. Probably because of the immense loss he experienced, Sơn took his spiritual refuge in Gautama Buddha. In truth, Sơn had a predestined karma with Buddhism. Sơn has said that since he was seven or eight, he started the habit of going alone into the temple’s garden with his books to study, read, think or copy the Buddhist mantra in Hán. Certainly Sơn absorbed Buddhist thinking, and it helped him connect with and understand his own heart as well the hearts of others, which is the most difficult task of one’s lifetime.

By the end of summer 1956, after graduating with a Baccalaureate I, Sơn was sent to Saigon alone to study philosophy at the Jean Jacques Rousseau School. From that time on Sơn had many long journeys. Sơn was no longer at the tender age of fifteen dreaming of being an adult. Sơn could thus fulfill his innate dream to “wander around, to just take off and move on. To move on in order to put some space between myself and home, and love; to move on to leave something behind. To move on to have letters to send home, to harvest more fond memories and more grief ” (10).

One characteristic of Sơn's was his liking of “fine food and nice clothing” (ăn ngon mặc đẹp). This feature must have originated from the schooling of his mother who was a typical Huế woman, aristocratic and dependable. In her opinion, when a meal was served it should not only taste good and include many dishes, but should also be artistic with all the colors of the ingredients blending in. Since ninth grade (French third grade), Sơn’s clothing was always neatly pressed, his shoes well polished, his hair sleekly combed. Whether he went out, or was at school or even stayed at home, every time he sat at the table, his etiquette was always gracious and elegant. He maintained this way until his death. That was why Sơn did not like to receive visits on his sick bed. Sơn did not wish to project an unpleasant image of himself in the eyes of others, especially of women. Because in his opinion: "The most beautiful creature, to me, is woman, with exquisite features seen from my own perspective" (11). And "(...) because it (beauty-ST) inspires people to perceive life as beautiful, as an existence worth contemplating. Life is worth living because there could not be a Promised Land better than this world for human to cherish. Home is she. Life arises from her. And since then, life learns to sing (to praise her)" (12).

In his adolescence, Sơn had his share of fluttering misty love, but nothing was concrete. Sơn’s whole generation seemed to grow up like that: “Loving flowing hair, a silhouette. Each day it is enough to see her face, to see her through the window. It makes my day. Pedaling my bike behind her without her knowing who I am. That is happiness” (13).

Regarding his physiology, Sơn had a peculiarity that not many people knew about. Unlike us, Sơn had three kidneys. Did this dissimilarity affect his characteristics and capabilities in any way? This is something only specialists could determine.

People who knew Sơn only later when he was frail would be surprised to know that in his youth Sơn was a strong healthy youth who loved sports. Not only did he practice track and field but he also took up Vô Vi Nam martial arts up to the brown belt.

One day on a trip home during a school break Sơn was practicing with Hà, his next youngest brother. Hà thrust his shoulder forwards throwing Sơn to the floor, and by accident Hà’s elbow hit Sơn’s chest breaking an artery in his lung. Sơn had to lie in bed for over a year to recover. This incident altered the course of Sơn’s life. As Nguyễn Du said:

Cho thanh cao mới được phần thanh cao

Ill-fated thou shall bear ills

Bestowed with grace thou shall live with grace

Bedridden for days and months on end, Sơn voraciously read Appollinaire, Marcel Pagnol, Jaques Prevert, Rabindranath Tagore, Marcel Proust etc. before he took up Nietzche, Nikos Kazantzakis, Albert Camus, Jean Paul Sartre, Heidegger, Merleau Ponti. Sơn particularly liked the works of Albert Camus, Vietnam's epic the Tale of Kiều by Nguyễn Du, and works on Buddhist philosophy, all of which he read over and over again. Not only did Sơn become immersed in literature and poetry, he also explored Vietnamese folksongs and African-American music: blues, gospel etc...

Sơn had more than once confided to his few close friends: “When I recovered, there was a new passion in me - music. Putting it this way is not quite accurate though: rather those desires, aspirations were buried in my subconscious, and only then they awaken and erupt” (14).

In one of his writings, Trịnh Công Sơn explained the path he had traveled: “I did not come to music like a person chooses a career. I remember I wrote my first compositions as a result of natural wants and urging desires that were inside me... That was in ‘56-‘57, the age of chaotic dreams, of passing naive illusions. At that age, as green and tender as still ripening fruit, I really loved music but I absolutely did not yearn to become a musician ...

"At the time, my father died, my mother was far away. Alone in Saigon I had to make all decisions for myself. The burden of life was still so light. There were times when I altogether dropped this game of romantic composing because of my stupid obsession with being the "outcast musician". I was sleepless night after night, restless for days and months. The more I wanted to forget the more distinctly my music surged, overwhelming me even when I sat, when I walked, when I slept... In later years, slowly a clear concept started to take shape: to live is to live with others, and to appreciate each other, we need to constantly express ourselves. Among the various means of expression --oral, written and others-- my soul is inclined towards lyric music. In this modest domain of the arts, I thought I could find freedom. In it I thought I could share with others the joy and sorrow of life." (15).

At the time, Trịnh Công Sơn was about to turn nineteen. He bore a heavy load on his shoulders, and his heart had been affected by the war that raged throughout his adolescence. Ahead of him, the world gradually unfolded, and the next vicious war was about to befall his people and himself. The dilemmas of life, the problems of war and humanity, the events of the era—all these things were intertwined and together forged in Trịnh Công Sơn a distinctive attitude before he officially began his life as a composer. How would he live and what would he do to justify his own existence?

Sâm Thương

April 01, 2004

To commemorate the third death anniversary of composer Trịnh Công Sơn

Translated by Vân Mai

___________________________

(1) The Munich Conference took place on August 29, 1938 between Hitler (Germany), Mussolini (Italy), Neville Chamberlain (England) and Edouard Daladier (France). Hitler warranted that Germany no longer intended to invade other European nations.

(2) On June 2, 1934, Germany and Poland signed the Treaty of Non-Aggression.

(3) On September 3,1938 in Munich, Hitler and Chamberlain (England Prime Minister) signed the Anglo-German Agreement, endorsing the mutual desire of the two people never to war each other again.

(4) German-Italian Alliance, May 1939: an alliance about military and economic wartime production.

(5) After Sơn, there are two brothers: Trịnh Quang Hà (1941), Trịnh Xuân Tịnh (1944); followed by five sisters: Trịnh Vĩnh Thuý (1947), Trịnh Vĩnh Tâm (1950), Trịnh Vĩnh Ngân (1952), Trịnh Hồng Diệu (1953), and Trịnh Vĩnh Trinh (1956), the youngest sister.

(6) Many Authors, Trịnh Công Sơn, the troubadour throughout many generations, Published by Trẻ 2003, p. 27.

(7) Emmanuel Mounier (1905-1950), French philosopher and writer. Founder of Esprit Journal, the mouthpiece of Personnalism Theory, who influenced Ngô Đình Nhu.

(8,9) Trịnh Công Sơn, Music and Life, Published by Tổng Hợp Hậu Giang, 1992

(10) Trịnh Công Sơn, Trịnh Công Sơn, Courting Life with Love, Sóng Nhạc, New Edition 1, 1999

(11) Trần Hữu Lục, If I cannot say it in music then I say it in painting, Tuổi Trẻ number 212 (October 23, 1990)

(12) Trịnh Công Sơn, Woman’s Beauty, Phụ Nữ TP Hồ Chí Minh, Spring 1993

(13) Trịnh Công Sơn, Introduction, Word of the Rose, poetry book of Trần Hữu Lục, published by Trẻ, 1998

(14) Unpublished private documents

(15) Trịnh Công Sơn, Sđd, Published by Tổng Hợp Hậu Giang, 1992

Các thao tác trên Tài liệu